7 Card Readers Tested

2,352 Test Runs; 3 OS Reinstalls; 1 Reader Knifed Open

Things Got Real-World

Following on our now-updated review of most major CFexpress card brands, we went ahead and tested the most popular card readers available, running them through real-world tests in addition to independently verifying their specs. Card readers often matter less than the cards themselves, but some people find a better card reader can save hours of time over the long-term. The slowest of the readers pulled files into Lightroom about 2/3rds slower than the fastest reader. But, of course, it’s complicated. Performance depends on whether you’re using a fast card; the fastest computer interface (Thunderbolt 3), the right cord, the speed of the drive you’re using; and the vagaries of firmware interactions between cards, readers, and the computers to which they attach. We’ve charted things out so you can choose a fast combination for your situation.

The Upshot:

The best CFexpress card reader is the $130 Prograde Thunderbolt 3 PG04. That said, you’ll get only about 20 percent worse real-world performance with the USB 3.2 Gen 2* reader from Delkin, costing only $55, the best value of the bunch. And if you don’t have a Thunderbolt 3 port, or an SSD drive, the performance difference goes away completely. The form factors of the readers are different enough to matter. The ProGrade remains our favorite due to a brilliant magnetic seating mechanism, but if you want two ports downloading at once, you’ll have the $200 Sonnet reader, and if you’re traveling with it, you might want the Delkin or Angelbird for the impressively small form factors.

The chart below shows the read speed of the six card readers tested (a seventh failed). This “pure” test measures the moving of 265 image files comprising 15.12 GB – a typical card download. The bars in green are readers that are USB 3.2 Gen 2 readers, and the blue bars represent Thunderbolt 3 readers.

| Reader | Cord | Interface | Price |

| Sonnet SF3 Series CFexpress/XQD Pro | USB C | Thunderbolt 3 | $200 |

| Atech Blackjet TX-1CXQ CFexpress Type B Thunderbolt 3 | USB C | Thunderbolt 3 | $150 |

| ProGrade PG04 CFexpress Type-B Single-Slot TB 3 Workflow | USB C | Thunderbolt 3 | $130 |

| SanDisk Extreme PRO CFexpress Reader | USB C | USB 3.2 Gen 2 | $70 |

| Angelbird CFexpress Reader | USB C | USB 3.2 Gen 2 | $65 |

| Delkin Devices USB 3.2 CFexpress Reader | USB C | USB 3.2 Gen 2 | $55 |

| Rocketek Cfexpress Reader | USB C | USB 3.2 Gen 2 | $37 |

The following image shows the seven readers tested. Starting from the top, and moving counter-clockwise, we have the readers from…

- Blackjet

- Prograde

- Angelbird

- Delkin

- Rocketek

- SanDisk

- Sonnet

USB C Only

Readers should note that no CFexpress card reader tested used an older USB cord, which renders obsolete a great percentage of the computers out there currently being used to manage photos and videos. This can be addressed with a <$10 Type-C to Type-A adapter, but tests were not conducted with these.

If your system lacks one of the factors in the list to the right to make things speedy, don’t despair. CFexpress is super-fast, and you will likely find that even operating with a USB 3.2 Gen 2 interface, using a non-Thunderbolt reader, you’ll be getting about 80 percent of the speed for the more optimized system (downloading to Lightroom at an average of 380 MB/s versus 473 MB/s). This is because the cards themselves don’t come close to using all of the bandwidth available in Thunderbolt 3. Most people won’t miss this difference. Any extra minutes wasted with a slower download speed are at least wasted long after the shoot, in post production. If you do wish to upgrade your system to take advantage of the better possible speeds, the first thing to attack would be moving from a hard drive to an SSD. A hard drive can easily slow your throughput down from the already lower 380 MB/s to just 100 MB/s. If looking to speed up post production, attack the drive first.

There are many, many factors that affect real-world speed. We found this out the hard way in our testing, needing to eliminate various barriers to do a completely fair test from the computer side. Transfer speeds are subject to shockingly long list of bottlenecks:

Speed of the receiving drive

Different chipsets

Controllers

Card reader firmware

Card firmware

Computer firmware

Ports

Cord type

Cord length

Cord shielding

Asset management software

Operating system processes

Memory card heat throttling

Chip efficiency performance changes due to heat

Card error correction routines

Card layer architecture

Throughput

So what’s the fastest card reader? For most cards and uses, it’s going to be the Prograde PG04 Thunderbolt 3 reader. It barely bested the other two Thunderbolt 3 readers tested, but those three together trounced the rest of the pack. But there are exceptions. For instance, when downloading a small number of files (26), the ProGrade reader is the worst. In fact, most of the Thunderbolt 3 ones fare poorly. The Angelbird reader really rocks here – coming in second – and it’s uses the slower USB 3.2 Gen 2 interface. Here is a chart of the time it took to download a small number of files (totaling 1.89 GB) in Lightroom…

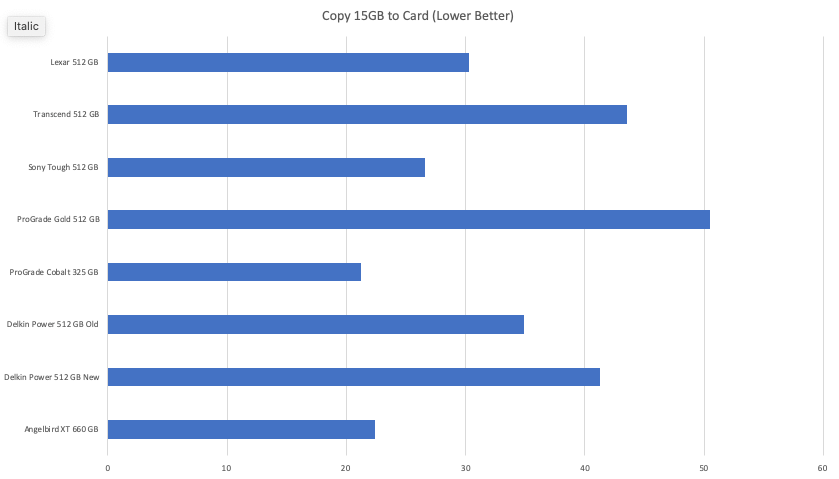

But if you up that number of files, the raw speed of the Thunderbolt readers starts to toll, as you can see in the chart below. The Angelbird reader, previously the fastest of the non-Thunderbolt readers, is now the slowest.

This has to do in part with a unique feature of the Angelbird reader, which encodes itself to the computer as being a type of “removable media.” Alone among the card readers, cards put into the Angelbird will show up in Lightroom in a special list above the hard drive volumes. This is where SD and CF cards typically appear, and it has the benefit of allowing Lightroom preferences like “Eject after import” to work with the card. The double-edged potential downside, though, is that the computer, Lightroom and card firmware will treat caching differently, and this is why you may experience very fast or much slower speeds under different circumstances, like the number of files you’re downloading.

But there’s another way to look at speed. You might download all of your files into a directory using the operating system, and then later ingest them into your favorite post production program. Or you might never ingest them into a digital asset manager (DAM) program, but rather edit files individually from a set of archive directories. To measure speed for people using those use cases, we charted the time it took simply to download the pictures by dragging the folder from the card onto the desktop of the computer, using the operating system to copy the files. The first set of results shown below are those from the smaller download of just 26 images. It shows that there isn’t much difference among the readers with this small amount of data, but that the non-Thunderbolt 3 readers do pretty well.

When looking across larger downloads, the earlier pattern prevails again, but the differences become exaggerated. The chart here shows average read time when moving files from the card reader to the computer with a 15.12 GB payload. Clearly, the Thunderbolt 3 interface for the Sonnet, Blackjet and ProGrade readers are allowing those to stretch their legs….

In a special circumstance, the fastest card reader by far would be the Sonnet dual card reader. If using both slots at the same time with the file copying method, the Thunderbolt 3 connection could carry all of the data of both channels at the same time, effectively doubling the speed – provided that the drive used to store the data is quick enough in writing it. This is a method used for managers of large projects, particularly those using large video files, ingesting from multiple cards at once.

The way *not* to measure card reader speeds is to use the computer applications that are designed to, well, measure card and card reader speeds. Blackmagicdesign Speed Test and CrystalDiskMark will give you read/write speeds for cards and readers, but it appears these don’t have direct applications for real-world performance of cards or readers when measured by factors such as how long it’ll take you to download a day’s shoot to your computer. The reason is that they are measuring one narrow variable – raw card speed – and not how that speed is affected by firmware interactions, performance against still-image-sized files, operating system calls, and potentially other ghosts in the machines. We did a complete set of diagnostics with these tools, and found the numbers to be the least reflective of user experiences. They are excellent tools to measure one thing, but that one thing proves to not control user available performance. Here is the chart of read and write speeds (in megabytes per second) from Blackmagicdesign Speed Test, averaging the performance across all eight cards tested for each of the card readers:

What did that chart tell us? It told us that write speeds are about equal across the cards, and MUCH lower than what the labels typically say. And that read speeds are also off from the claimed specs, but primarily limited in practice by whether your reader uses a Thunderbolt 3 interface or not. That’s not a lot of information for spending a few hours running cards through readers. The gist of this is that if you want to test your own card at home, these computer program tests aren’t going to be too helpful. The better information for your own card would be found by timing the card downloading a specific amount of data using the way you normally ingest photos. That time data will be a practical measure, and can be compared to the benchmarks in this comparison review. This is why we explicitly mention how much data we’re transferring with each set of tests.

A more obscure use case is the need to write files onto a card from the computer. Most users will be writing with the camera and reading to the computer, but in case you do need to write directly to the card, there isn’t much of a difference among the readers – even between Thunderbolt 3 readers and the others. The cards themselves become the limiting factor.

Here is a listing of the cards tested and plainly some have not been optimized for direct writing from the computer. Angelbird XT series and the ProGrade Cobalt series show vastly better performance.

Meet the Card Readers

ProGrade:

Factoring in both performance and cost, the ProGrade reader is a pretty easy call as the best option, provided your computer has a Thunderbolt 3 port. It costs about twice the amount of the USB 3.2 Gen 2 card readers, and is usually the fastest reader among all of the lot. We were taken by this reader because of some of its functional design elements.

A unique feature: it has a strong magnet on the bottom, so it can be stowed in all sorts of places, even upside down under your desk with the port peeking out. ProGrade provides a metallic sticker that you can adhere under your desk, or anywhere else, to which the reader can then securely affix. Pictured above, the reader is solidly planted on a currently-empty monitor swivel.

The form factor is large and blocky – not the prettiest of the readers. Its cord, while longer than some, is still fairly short, as is required of most Thunderbolt 3 devices – so sometimes stowing away while still connected can be difficult. One word of warning: it probably is not a good idea to stick the reader onto another piece of hardware, like a computer or hard drive that also generates heat. The CFexpress readers can get toasty.

A minor quibble: when inserted, the cards fit perfectly flush with the opening of the card reader, so when you want to eject, you need to use the very tip of your finger in that slot, which requires some precision.

ProGrade started up not long ago, founded by executives that left Micron when the flash memory giant sold its Lexar brand to the Chinese company Longsys. ProGrade quickly made a very good name for themselves and should not be confused with the current Lexar manufacturer, which has had some issues. ProGrade makes a USB 3.2 Gen 2 version of this same reader, which was not tested. If looking for the best speed, make sure the product packaging mentions Thunderbolt 3.

Delkin:

The Delkin reader is so light that it’s difficult to get it to sit flat on the table when the USB cord doesn’t naturally lie at the same angle. It is the size and shape of a wide cigarette lighter, complete with the pivoting cap. The cap in this case, is a rubber-like material, affording some dust and moisture protection when hurled around in a backpack.

It is the fastest of the USB 3.2 Gen 2 readers in most tests, and even the fastest Thunderbolt reader would be only about a quarter faster when reading cards. The Delkin will eat up 15 GB of images in about 18 seconds. The ProGrade reader will do it in about 14.

It has a positive push-in-to-latch and push-in-again-to-unlatch mechanism that leaves a small amount of the card outside the reader, which makes pushing for ejecting one-handed.

BlackJet:

The Atech Blackjet reader makes the ProGrade reader look thin: it is large, blocky, metal and a good bit heftier. It has nice rubber feet, so that – combined with its weight – when you push a card into its maw, it won’t simply scoot back across the desk. It is our second choice among the Thunderbolt 3 readers, showing impressive speed and a slightly higher cost ($150) than the ProGrade reader ($120).

The Blackjet reader actually beats the ProGrade reader for copying files to a computer, but only by 1.5 percent. In the Lightroom ingesting test, it is 2 percent slower. Neither could be noticed if not holding a stopwatch.

Sonnet:

We really wanted to like the Sonnet reader, and we do, but it suffered from several hiccups that might have been firmware-related. There were early versions of the Delkin and Angelbird cards that wouldn’t be recognized by it. Firmware upgrades from both companies rectified that issue, but among the Thunderbolt readers the Sonnet reader was the most finicky, despite having the most frequent firmware upgrade history.

Its speed is about 5 percent off the fastest reader – which isn’t bad at all.

The real claim for the Sonnet is having dual slots. This is the only reader than can read from one card and write to the other simultaneously. A more likely use case would be downloading large video files from two cards at once. The Thunderbolt 3 standard supports this, allowing for an almost doubling of throughput when having to move many or massive files.

The reader has its own power supply, the only CFexpress reader tested that does not rely on the bus power from a computer’s Thunderbolt 3 port. This puts less juice through that system and keeps the computer itself cooler. The Sonnet reader also has a screw-in safety mechanism to make sure the USB C cord doesn’t get removed by mistake mid-transfer. Only the Angelbird reader’s cord is as well secured.

Like the BlackJet reader, it seems designed to shed heat, employing a metal casing and shallow fins.

Perhaps the best feature of the Sonnet is the fact that it has two Thunderbolt 3 ports, allowing it to be in the middle of a daisy chain of up to six devices. The other readers, lacking the extra port, have to be at the end of the chain, which may conflict with another device that also lacks a second port.

Angelbird:

The Angelbird card reader is among the fastest of the USB 3.2 Gen 2 readers when copying files to the computer. It is a bit different, though. It acts as a removable device where the other card readers present the cards to the computer as SSD drives. Due partly to this, it isn’t the fastest for downloading to Lightroom. The ability to be seen as removable media is handy in some ways, though, such as allowing Lightroom to automatically dismount the card after finishing up its import.

The industrial design is pretty, and the reader will seat above or below another Angelbird reader, such as their excellent Dual SD card reader (reviews on those coming soon). In fact, they provide in the box special velcro straps so these devices can be tethered together. The case is metal, with a deliberately distressed finish, much like the Angelbird CFexpress cards.

Its USB C cord fits into a recess in the back, locking it into place so it cannot be mistakenly knocked out during transfers.

The size of the Angelbird reader is as small as the Delkin, making it one of the two we’d most recommend for travel.

SanDisk:

The SanDisk reader is perfectly serviceable. It is only about 5 percent slower than the fastest USB 3.2 Gen 2 reader, and it performed very consistently. It is roughly the size and shape of a computer mouse and a bit heavier than the other two USB versions.

It sells for $70, which is a pretty good deal, although $5 more than the Angelbird reader and $15 more than the Delkin.

The LED light that shines next to the slot is a bit bright for taste, but it is functional in that it actually shows writing and reading activity.

The one problem we had with this reader was the included cord, which proved to have connectors that seemed a bit over-sized. It fit the reader itself surprisingly snugly, but when attaching to multiple computers, more force was required than we were willing apply to our delicate daughterboards on which the USB ports are soldered. This was easily solved by using a different USB C cord and not borrowing the trouble.

Service Issues

As is normal when we torture test a dozen or so items, we found some problems, and these allow us to see how companies react to service issues.

Angelbird

While Angelbird card reader is about tied to be the fastest of the non-Thunderbolt 3 readers when copying files directly to a computer, we were surprised to discover in the Lightroom test that the reader was having a speed issue. So we contacted the firm in Austria, and their responsiveness was notable. A marketing rep immediately passed us on to a more technical representative, and we were able to establish that the speed difference had to do with the unique ability of Angelbird’s reader to function as “removable media.”

In reviewing CFexpress cards and readers, we’ve seen that Angelbird, like Delkin, is a smaller firm, and their market strategy is to forge personal relationships. This is refreshing in an industry typically dominated by firms that unintentionally separate themselves from their users through the use of national subsidiaries, distributors and other channel-dwelling companies that create a fog of inaccessibility. This gives an advantage to some of these Western manufacturers who seem more comfortable jawboning on the phone about firmware choices made. This is what let us get to the crux: while the Angelbird reader is among the speediest for downloading pictures directly to the computer, it’s also the only one that will act as removable media in Lightroom, and ingest more slowly as a consequence.

One additional note on the Angelbird reader: Unlike most of the others (Sonnet being the other exception), its firmware is user upgradable.

LEXAR

The Lexar 512 GB card we tested started behaving erratically. For a time it seemed to have two performance levels, a fast and a slow one, and would roughly alternate between those states. We were able to speak to a support person in California and established that it was indeed acting inappropriately. The service rep suggested we return it to the retailer, however, as Lexar returns tend to be slow. We’d find out soon why. After hanging up, we got an email from Lexar indicating that its Chinese parent company, Longsys, is under US restrictions that prevent the firm from delivering replacement products to end users.

Indeed, the restrictions were covered by a PetaPixel story in 2018. But while the CFIUS restrictions put in place in August 2018 appeared to have caused the issues raised in that story, Longsys had since represented to investors, in presentations still available on the internet, that it had put all of its regulatory issues behind it. In fact, consulting the series of US Treasury Department databases on listed entities fails to pull up Longsys as a current entity in poor standing. Inquiries to Treasury were not returned at the time of the publishing of this review.

Lexar responded to our questions by email, stating, “The restrictions do not allow us to send physical product directly to our end user customers. We are still allowed to provide stock to our authorized resellers/retailers, however.”

We will continue to look into the details of Lexar’s service capacity, but in the meantime it is likely safest to use a retailer that accepts returns, and to perhaps avoid Lexar products until the issues are cleared up.

SanDisk

Reviews on Amazon showed that earlier purchasers sometimes complained about a loose cord connection. The version we purchased, the better part of a year after these reviews first appeared, seemed to overcompensate for this. The USB C cord that came with the reader was quite difficult to insert into the reader, and the other end proved impossible to insert into the computer without the possibility of dismounting the port connection from the board on which it is attached inside the computer. Rather than risk that computer-killing possibility, we just used the cord from the fastest card reader as a replacement.

We did not contact SanDisk support, as sending a new cord was unnecessary, but user reports elsewhere indicate that they are responsive, quick to send out replacement materials when available.

Rocketek

This is the cheapest of the readers available ($37), and probably for good reason. There are about a dozen brands, all apparently Chinese, that appear to provide a bare bones reader, so we purchased one to throw into the mix. It just didn’t work, not even lighting up the double LED light to the left of the slot. A few judicious blows in the right place with a blade opened up the case to show the device’s entrails. After some careful nudging here and there with the connections, the now-naked reader was able to show up as a device on the computer, but would fail to mount cards and show errors if an attempt to format was made. Of course, do not open your reader at home, especially when running the device outside its casing on a self-powered Thunderbolt 3 port. To lessen the clutter in our charts we excluded the Rocketek from the data.

A paper card that came in the box indicated that any concerns could be addressed to a Steven at a Gmail address. We have not heard back.

Testing Methods

Card readers deal with many different brands of cards and firmware; different user workflows; and exposure to other systems that have various throughput limitations, such as cords, interfaces, ports, hard drives and a dozen or two other obscure influences.

Our testing showed that, unfortunately, all of these other factors vastly affected the results. You can simplistically test each reader against one card in one system using a program like BlackMagicDesign Speed Test, but the information you get won’t be but so useful in terms of predicting real-world performance.

As seems almost normal, as we embarked on time-consuming series of tests, we discovered our tests were being limited by unexpected factors. These forced us to abandon a few days of data collection so could remake our computer system in order to ensure that none of the receiving technology exerted limits on our data. That done, we collected eight very different CFexpress cards to put through all of the tests (pictured below), allowing for us to both report average results, as well as make note of any special circumstances where a particular card had a firmware interaction with a particular reader.

To reflect the different workflows of readers, we did three main tests across the readers and cards:

- A pure copy of files from a card to a computer SSD drive (both a small and large import of stills images).

- An ingest of those same sets of photos into Lightroom through the Lightroom Classic interface.

- A write to the cards of those same sets of images. This latter test is a more obscure use case, but we were curious if it would give us some intelligence with which we could update our card comparison review (it did).

We also did a full comparison of all cards in all readers using a computer program that measured card throughput through the USB or Thunderbolt interface, depending on the reader.

Other information used included looking up user reviews on Amazon.com to see if a greater number of users had certain common problems with cards or readers; and personal interactions with service staff at the manufacturers.

Conclusions

Our earlier review of CFexpress cards showed that – at best – cards were providing about 1/3rd of their claimed write speed ratings when shooting stills a very fast clip. Generally, on the card reader side of things, we find that the fastest reader can provide about the same rate of real transfer power when doing a simple file copies. When using a Thunderbolt 3 port, these file transfers are about 20-30 percent faster than when using a USB 3.2 Gen 2 port. The upshot is that cards generally matter more than card readers, as the cards are a more limiting factor. That said, if you have a Thunderbolt 3 port on your computer, getting one of the more expensive readers that exploits it will give you a real boost in exchange for paying 2-4 times the cost of the other readers.

Recommendations

Factoring in performance and cost, the ProGrade reader is a pretty easy call as the best option, provided your computer has a Thunderbolt 3 port. At $130, it costs about twice the amount of the USB 3.2 Gen 2 card readers, and is usually the fastest reader among all of the lot. We were taken by this reader because of some of its functional design elements, in particular the magnetic base that allows it to be placed anywhere on a desk, including upside down, under the desktop. It also has a longer cord than most Thunderbolt 3 devices, allowing more desk placement flexibility, but still somewhat limited due to Thunderbolt’s sensitivity to cord length limitations. The best alternative to the Prograde reader is the Atech Blackjet reader, which costs $20 more, is almost as fast, and has a metal exterior that may be better at heat exchange.

Among the non-Thunderbolt options, the Delkin reader is fast, consistent, portable, and easily the most protected from dust and moisture, with it’s Tic-Tac box emulating rubber cap, making it the favorite for travel. At $55, it is also the cheapest of the card readers that actually worked. The Angelbird is a good alternative, being faster at direct downloads to the computer but slower in downloads done through Lightroom. It costs just $5 more. The Angelbird industrial design is probably the best looking of all of the readers, provides the most secure cord connection, recessed into the case, and provides a write protect switch on the reader itself. It also is the only reader that presents itself as removable media to the computer which has some benefits in Lightroom, but also makes it slower to ingest files into Lightroom.

* USB standards names are created (and frequently changed) by an industry consortium of very smart engineering firms that, when operating collectively, act as branding numbskulls. Don’t be overly confused by the different USB standards thrown around. What was once USB 3.1 Gen 2 is now called USB 3.2 Gen 2. You needn’t worry about these distinctions because all of the available CFexpress card readers use the latest standard, even if they call it one or the other. To add further confusion, the USB C cord refers to the connector at the end of the cord, and not a particular USB standard of data transfer. This is why the USB C cords are used for both the USB 3.2 Gen 2 interfaces and the Thunderbolt 3 interfaces, as both use the same cord. Got it? Good.

Tilt Shift Calculator

Tilt Shift Calculator POWERING THE EOS R5

POWERING THE EOS R5 R5 Portal

R5 Portal Camera

Camera Lens

Lens Batteries

Batteries Memory Cards

Memory Cards